How To

Structuring Adult/Youth Collaboration in Ambitious Digital Learning and Making Projects

Rafi Santo - New York University

Digital learning can involve youth developing ambitious collaborative projects alongside educators, including massive ‘maker' productions, full-featured apps, and digital activism campaigns. This resource explores how to consider adult/youth collaborations on such projects.

What’s the Issue?

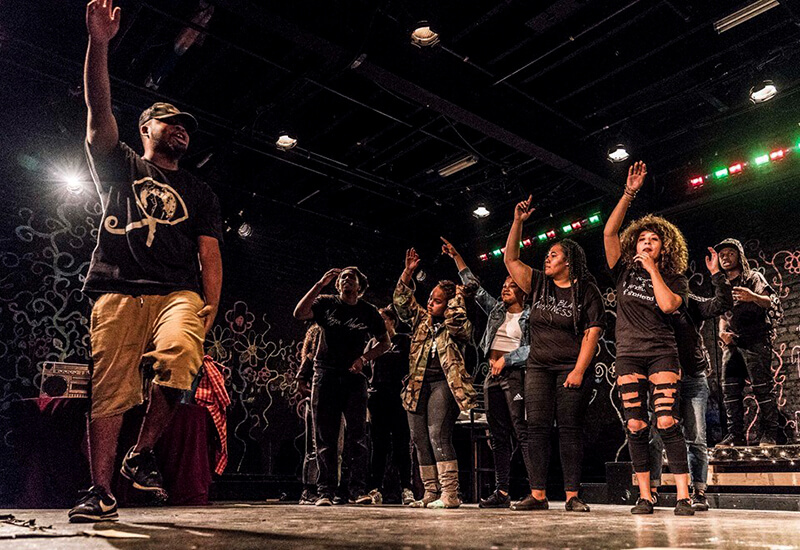

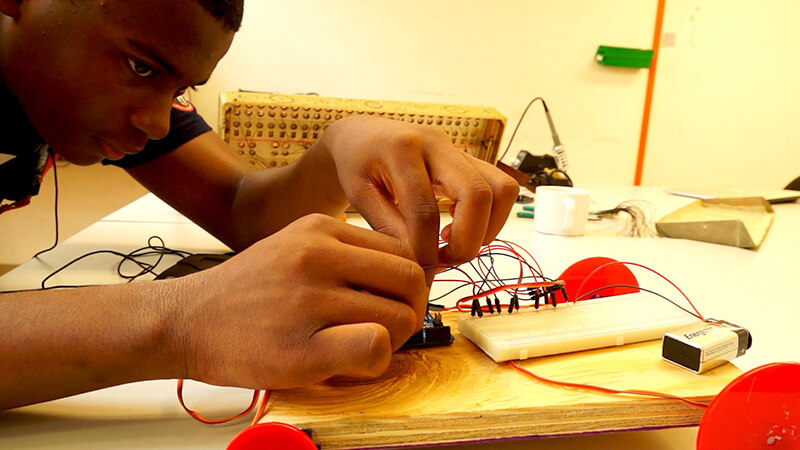

Youth-serving organizations that incorporate creative production in digital media often have young people engage in ambitious collaborative projects alongside educators that go beyond what individuals could make on their own. Large-scale events, massive maker productions, full-featured apps, digital activism campaigns and complex video games are all examples of ambitious projects that youth and adult educators might work on together in the context of digital learning and creative production-focused youth programs.

In this resource, we explore what this can look like in practice; we point to real-world examples, discuss the value of this form of creative, collaborative youth pedagogy, note challenges, tensions and questions, consider the role of technology, and share reflections for consideration by educators and organizations that want to explore this approach.

What Does it Look Like?

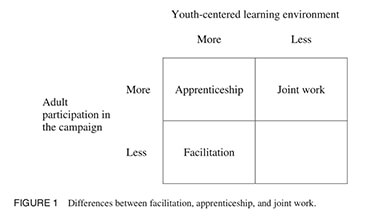

There are many ways to structure adult-youth collaborations in informal learning programs. In his study of youth activism programs, Ben Kirshner (2008) outlines a framework for different forms of collaboration, distinguishing between facilitation, apprenticeship, and joint work. Some of these approaches have greater degrees of adult participation, some have more leadership from youth themselves, and some aim to achieve a balance of the two.

Framework on youth-adult collaboration, adapted from Kirshner (2008).

Guiding Questions

- If you haven’t done this before, what’s a way to start small

and pilot this sort of approach? - How do you envision the mix of adult and youth participation?

When is an approach of guided facilitation more appropriate,

when should things look like apprenticeship, and when should

educators and youth be engaged in joint work? - How will decision-making and project management be structured,

and who will be responsible for what? - How will you balance goals such as youth identity development,

agency, skill attainment, and public impact ?

In a facilitation approach, “adults [seek] to be neutral facilitators of a youth-led process” (p75), doing things like guiding conversations, sharing routines for decision making or project management, and making sure youth have resources they need, like equipment (e.g. video cameras, computers), space to do work together or logistics like transportation.

In apprenticeship approaches, youth and adults share many roles and activities, with adults actively giving feedback and sharing their views on how a project might work best, participating with youth in decision making around a project, helping complete tasks, and tailoring activities to the skills and developmental capacities of the youth present. In this approach, educators would still lead structures, like group sharing activities, to help create a sense of belonging, or ones that actively helped guide decision-making in a way that was inclusive of all youth that are involved.

In projects that take a joint work approach, the success of the project itself is emphasized in a way that might mean less tailoring of activities to the skill and interest-levels of the youth themselves in favor of ensuring a project’s completion at a high level of quality. Like the apprenticeship approach, in joint work youth and adults participate together in activities like decision-making and project development, but there might “be little effort to position youth as leaders of the project, distance adults from the project, or operate as if one group or another were supposed to be in charge” (p85).

These forms of collaboration aren’t mutually exclusive within a given project. Projects might move from one approach to another at different phases of the work. To explore what this looks like in practice, look to three case examples – AS220’s FUTUREWORLDS program, Beam Center’s ‘learning productions’ pedagogy, and WMCAT’s video game design studio.

What Does it Lead to?

Ambitious educator/youth collaborations are often complex, high-resource endeavors that take lots of staff and youth time, specialized expertise, and often expensive equipment or software. Given that, educators might ask themselves — is this really worth the trouble? We believe it is, because there are many important outcomes that result from these types of projects. These include:

- Skills like collaboration, negotiation and communication, problem-solving, role specialization and learning to work in complex teams, design thinking, empathy and the ability to think about and determine audiences and community needs.

- Contributions and impact on local communities.

- A greater sense of pride for the youth involved than might be possible in individual projects.

- A view into professional practice in a domain for youth involved.

- Greater youth motivation and interest that’s generated by taking on an ambitious goal.

- Collective agency among a youth community and sense of collaborative accomplishment.

Tensions and Challenges

It’s helpful to note that some ‘bumps in the road’ are natural parts of ambitious adult/youth creative collaborations. Acknowledging these can go a long way to having both educators and youth come in with appropriate expectations around what it can take to engage in this sort of work, and help those that are guiding the process to design with tensions in mind.

- Roles and Responsibilities. First and foremost are questions of roles and responsibilities. Who has power to make decisions, and about what, in the context of a collaborative project? What are adult educators responsible for, and what is up to the youth leaders? Who is accountable for what, how do they know, and what happens when not everyone is able to contribute in the way they thought they’d be able to? A lack of clarity around these sorts of issues can sometimes lead to a project feeling like it’s going off the rails.

- Compromises and Buy-in. For creative youth that might be used to making stuff on their own, it can be a new experience to cede their own individual ideas and time on independent projects in order to help bring a bigger vision to life. And while a big project at the beginning can be really exciting when all sorts of possibilities are on the table, when things get more complex and the ‘rubber hits the road’, youth motivation can dip. Educators often need to support youth to meet the challenge of actually bringing a project to life, even if some of their ideas didn’t make it in the final version.

- Managing Scope. Large projects can often take on a life of their own, and youth that haven’t had experience with project management might come up with big ideas that may not match the time and resources available. If that’s not reigned in and the project gets underway, when things can’t get done everyone involved can get disappointed. Depending on the perspective and approach, having youth experience these sorts of lessons can be part of the process. Having mechanisms in place to reflect on feasibility of designs is not just good practice, it can also help reduce the number of late nights that staff involved might have to take as the project nears its completion.

Related Resources

- Ben Kirshner’s article on

three forms of adult/youth collaboration in youth activism

organizations - Tom Akiva’s article on

youth involvement in programmatic decision-making - Sara Vogel and Judy Perry’s article on adult/youth collaboration in designing mobile games

- Tom Akiva’s article on

adult-youth partnerships in OST organizations.

The Role of Media and Technology

While there is a strong tradition in youth development organizations of engaging in ambitious adult/youth collaborative projects, activities like this that are focused on digital and creative production disciplines, like game and app design, media arts, film, music and maker, are distinct in a couple of ways that should be discussed and leveraged:

- Incorporate specialized technology expertise of youth and adults involved. Many youth, or specialized educators like teaching artists or technologists, can bring specific expertise in certain technologies or disciplines. These are resources to build off of!

- Adapt design processes coming from digital culture. One of the strengths of media and technology disciplines is that they have strong cultural practices around collaborative production, including things like the design thinking process, attending to audiences and users, open collaboration and a range of ideation techniques.

- Consider mixed media approaches. If your organization engages youth in multiple forms of media, arts and technology making, consider what it can look like to create collaborative projects that span creative disciplines.

- Use tech tools for collaboration and project management. Support youth to engage in standard professional practices by using tools like cloud-based file-sharing, collaboration platforms like Slack or group email lists, and group project management tools to keep things on track.

- Document project process with rich media. Using film, photo and audio to capture the process of creating an ambitious collaborative project can help both to reflect on how things went after the project is complete, but also to give outside audiences a ‘behind the scenes’ view into what it takes to pull these sorts of projects off.